[Link to “Surprising History in Yucatán” — Introduction to the Series]

November 20 is Revolution Day in Mexico, an important public holiday. Yucatecans would change the date to June 4.

History books say the Revolution began on Sunday, November 20, 1910, when Francisco I. Madero sent this message to the Mexican people from his exile in San Antonio, Texas: “Do not hesitate a moment, take up arms, throw out the usurpers of power, recover the rights of free men ….” Perhaps to Madero’s amazement, they did it. A year later he was President of Mexico.

But Valladolid claims an event, months earlier, as the real beginning. Journalist and historian Carlos R. Menéndez memorably called it “the first spark of the Revolution.”

Protests had been buzzing because of the unending re-elections of President Porfirio Díaz and his allies through rigged elections and harassment of opposition candidates. In Yucatán, Valladolid was a hornet’s nest of discontent.

A local opposition activist, Maximiliano R. Bonilla, had been arrested and imprisoned in 1909, along with hundreds of others, for electoral activities. Official results of that year’s election had the Díaz candidate for governor, Enrique Muñoz Arístegui, winning by a ludicrous 76,791 votes to his opponent’s 5. Freed after the election, Bonilla and other members of the anti-Díaz party met and plotted through the spring of 1910. On May 10 the conspirators, including “pacified” Maya leaders from the region, signed a manifesto called the Plan of Dzelkoop, named for Bonilla’s ranch near Valladolid where they met.

The Plan was essentially a protest against election fraud, plus vague statements about despotism and exploitation of Indians. The leaders — Miguel Ruz Ponce, Atilano Albertos, and others in addition to Bonilla — were mid-level planters and merchants, not fire-breathing revolutionaries. They recruited Cresencio Jiménez Borreguí, a leading ally of Madero, to edit their manifesto, printed up a few dozen copies, and mailed them out to government officials and the press.

The thing caught fire. On June 4, 1,500 civilians rose in arms to take Valladolid. They included many indigenous villagers and plantation workers, whose leaders included José Crisanto Chí and José E. Kantún. An assault on the military barracks began at 3:00 a.m. Attackers shot the man on guard duty and three other soldiers. They brought out the hated district political strongman, Luis Felipe Regil, in his nightclothes and hacked him to death with machetes.

Miguel Ruz Ponce read out the pronouncement in Valladolid’s main square. The victorious rebels began erecting barricades and digging defensive trenches, took up railroad rails, cut telegraph lines, and emptied the municipal treasury. They celebrated with music, fireworks, and drink.

News of the revolt inspired wild rumors in Mérida and a sensation throughout Mexico. Reports of thousands of attacking Maya spread worldwide.

Governor Muñoz Arístegui responded at once to prevent the revolt from spreading. He dispatched Col. Ignacio A. Lara with 600 national guardsmen and sent a wire to President Díaz. On June 7, skirmishes took place in the rebel-occupied approaches to Valladolid at Tinum, Uayma, and Pixoy. The rebels fell back before the militia. Fresh Federal troops disembarked at Progreso — 600 men of the 10th Infantry Battalion, commanded by Col. Gonzalo Luque — and quickly arrived on the scene. In Santa Cruz, Quintana Roo Territory, Gen. Ignacio Bravo mobilized the 25th Federal battalion and began a forced march toward Valladolid.

By the afternoon of June 8, Valladolid was under siege. An attack began the next morning. Reportedly, many defenders were drunk at the time. It was over by early afternoon. Federal troops sacked shops and killed some residents. Although there was never an official report, about 200 rebels were killed, 500 wounded, and another 600 taken prisoner. The government troops suffered 38 dead, and the 52 wounded included Col. Lara himself. Elderly Gen. Bravo arrived two days late, enraged that Col. Luque had not waited for him.

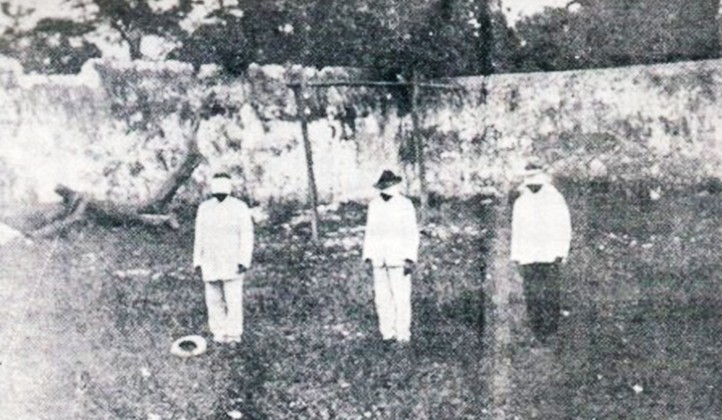

Bonilla, Albertos, and Kantún were taken prisoner. After a summary court martial, they were executed by firing squad on June 25 in the patio of the ex-convent San Roque. Ruz Ponce and some other leaders escaped into the eastern forests. High-ranking prisoners were sent to the fearsome fortress of San Juan de Ulúa in Veracruz and to a military prison in Mexico City. Large monetary fines were imposed, and 75 prisoners went to the state penitentiary in Mérida. The rest were drafted into the Federal army or, if unfit for service, sent to Gen. Bravo’s Santa Cruz labor camps.

Maximiliano R. Bonilla, Atilano Albertos, and José E. Kantún moments before their execution, Valladolid, June 25, 1910.

(Photographer unknown. From Carlos R. Menéndez, La primera chispa de la Revolución Mexicana, 1919.)

The rebellion did not spread beyond Valladolid. It lacked effective planning, leadership, organization, and arms. However, it was important for its size and for the response it provoked. Although the government tried to portray the rebels as just a mob of bandits, the overwhelmingly violent response demonstrated real political concern.

Other states have proposed their own uprisings as the beginning of the Revolution. Perhaps the best candidates are the strike at Cananea, Sonora and rebellion in Acayucan, Veracruz, both in 1906. But given its size and violence, Yucatán’s claim is plausible. All contributed to raising the people’s determination to overthrow Díaz and the old order.

It is ironic that the “first spark” was struck in Yucatán, where the real Revolution arrived only very late. While chaos and violent change swept the rest of Mexico after 1910, Yucatán remained mostly peaceful, experiencing what historians call the prolonged porfiriato. Episodes of insurgency took place — most notably in Temax, Peto, and Ticul — but the small, all-powerful plantation class maintained its control, resisting even modest reforms.

In a state with terrible labor conditions and a long tradition of revolts, why was there no effective mobilization from below? The reasons are complex.

The elite class continued to derive great profits from henequen, and they used state and private police forces to prevent disruptions. Yucatán’s poor means of communication — isolation, bad roads, restricted mobility — hampered organization and limited news of the Revolution in the rest of country. Yucatecans, with their tradition of separatism, had a profound distrust for anything coming from Mexico. And the long and catastrophic Caste War made everyone wary of any kind of rebellion.

The people one would most expect to rise up, the cruelly exploited plantation workers, were a fragmented and heterogeneous force of deracinated Maya, contract workers, deportees, and convicts, all beaten down by high death rates. Peasant leaders with the abilities of Francisco “Pancho” Villa or Emiliano Zapata did not emerge.

No strong, educated middle class or organized labor force existed to provide leadership. The middle class made up no more than 5% of the population, and most were dependent on henequen. Some urban workers did make efforts to organize, but with little industry other than henequen, their numbers were small, mostly railroad and dock workers. Cultural isolation kept people apart. Mestizos and urban workers were entirely separate from rural peasants in their identities and had no interest in the Indian countryside.

So when the Revolution finally did arrive in Yucatán, it came from outside. Although it eventually produced profound changes, it was relatively nonviolent, and the Peninsula was spared the ten-year conflict that took the lives of more than a million Mexicans.

Monument in Heroes’ Park, Valladolid, where the leaders of the June 1910 revolt were executed.

(Photograph by the author)

In early 1915, the head of the main Constitutionalist faction of the national government, Venustiano Carranza, decided he could not ignore Yucatán. He needed funds from the henequen exports for his offensive against Villa and Zapata. He sent military governors to impose reforms and taxes, as into a conquered territory. The oligarchs succeeded in convincing the first one to overlook the exploited workers, but the second, General Toribio de los Santos, showed he was serious. On arrival, he attacked the elites as parasites and insisted on forced loans, funding for schools, fair pay for workers, an eight-hour workday, and land redistribution. His term lasted less than two weeks.

The military commander of Mérida, Col. Abel Ortiz Argumedo, backed by the henequen millionaires, revolted. He took the city on February 12 and declared himself governor. He sent De los Santos packing and sank a Federal gunboat at Progreso. A Yucatecan delegation in the United States sought to negotiate a loan, buy arms, and become a protectorate. It was the 1840s again — Yucatán on its own, claiming sovereignty if not outright independence from Mexico.

Carranza reacted swiftly. He instituted a naval blockade, but the United States, concerned about interruption in the henequen supply, forced him to lift it. He ordered the military governor of nearby Quintana Roo, General Arturo Garcilazo, to put down the revolt, but Garcilazo decided to ally himself with Ortiz Argumedo. And in the definitive move, Carranza sent in a large military force led by one of his best generals — Salvador Alvarado.

At the beginning of March, Alvarado and 6,000 Federal troops arrived in Campeche. They were well trained, experienced, and supported by artillery and aircraft. Joined by a 900-man brigade of Campechanos, they marched north.

Lavishly funded and buoyed by enthusiasm for Yucatecan independence, Ortiz Argumedo managed to raise some 4,000 men to oppose the invaders. Many were students, urban workers, and the sons of aristocrats, poorly trained, armed, and led. On March 14, there was a battle at Blanca Flor on the road to Mérida, and then a skirmish at hacienda Pocboc. Fierce all-day fighting took place at Halachó on the 16th. On the morning of the 19th, Alvarado marched peacefully into Mérida. The city appeared to be deserted, the wealthy elite fled, Ortiz Argumedo on his way to Cuba with the state treasury, frightened citizens hiding behind locked doors.

But Alvarado was resolved to win over the Yucatecan with a policy of lenience, not punish them for disloyalty. The day before his arrival, he had leaflets dropped from an airplane — a sensational novelty — promising fair treatment. The only casualties were four of his own soldiers shot for looting and two others hanged as examples in a public street for rape.

A reputation for cruelty later attached to Alvarado cannot be justified. Without question, his troops did perpetrate some outrages, murdering the wounded and violating civilians, standard practices in warfare at the time. There is no evidence Alvarado condoned or encouraged this. At Halachó he personally intervened and rescued a large group of prisoners lined up for firing squads. He did impose some exemplary and justifiable punishments during the early days. Leaders of the revolt were jailed and some assets expropriated. General Garcilazo was shot as a traitor. But in reality Alvarado was magnanimous — most prisoners were quickly released, and violence was far lower than elsewhere in Mexico during the Revolution.

Carranza appointed Alvarado the civil governor of Yucatán state and military commander of the Southeast. Among his first stunning moves, Alvarado disbanded the repressive militia and police units and, with a law canceling inherited debts, did away with debt peonage. The effect was to liberate 60,000 workers from slave-like conditions to become participating citizens.

An outsider from northern Mexico, Alvarado tried diligently to understand the local situation and win acceptance. Contemporaries described him as a polite, dignified man with simple tastes. A widower when he arrived, he married a Yucatecan woman of modest means, Laura Manzano, after a lengthy and very proper courtship.

Despite sometimes extremist rhetoric, this was a middle-class revolution, with concern for property and conventional respectability. Alvarado actively suppressed revolutionary activity among the rural poor. He had a talent for forming coalitions and focused on inclusiveness and alliances. Some of the deposed wealthy citizens returned from their exiles in Cuba and New Orleans, and he sought to include them in his government along with other respected Yucatecans.

Alvarado worked to maintain a delicate balance between redistributing land and maintaining the vital cash-producing henequen business, doing good for workers while getting a better deal for growers. The state essentially took over the henequen export business, ending foreign control and the secret deal with International Harvester. New policies and institutions stabilized henequen prices at higher levels fairer to growers. Alvarado likened these actions to trust-busting in the United States, which he admired.

While acting to dismantle the huge feudal estates, he strongly supported mid-rank growers, viewing them as modern capitalists. He favored income-producing estates over village milpas. His model was the North American society of middle-class businesses and farmers, a concept foreign to Yucatán.

Most importantly, Alvarado formulated a program for the Revolution where none had existed. Leaders had previously made clear what they opposed and hated, but without stating specific goals. In his short governorship — a few months less than three years — Alvarado was extraordinarily effective in setting up a clear and transformative program for Yucatán. His plans became a success model for the nation, coloring Mexican policies even today.

Insulated from direct control by Carranza, backed by an army, without competing revolutionary forces, and with henequen income at record highs, Alvarado was able to carry out many of his plans. As examples, consider his accomplishments in education (a thousand new schools, free, secular, and compulsory), women’s rights (coeducation, employment of women in government, the first feminist congress in Mexico), and labor (formation of hundreds of workers’ unions, reform laws later adopted nationwide). His efforts to suppress religious fanaticism, which he believed contributed to the oppression of women, and his morality campaigns — against alcohol, prostitution, gambling, and bullfights — were unpopular and less successful. Ahead of his time and with his term cut short, Alvarado failed to realize his innovative plans for land redistribution, modernized agriculture, and coordination of regional development.

Carranza, now president, forced Alvarado out in 1918, in part because of pressure from the United States. Alvarado became entangled in political disputes, opposing his long-time rival and Carranza’s successor, President Álvaro Obregón. In open warfare over presidential succession, Alvarado found himself on the losing side and fled toward Guatemala. He was overtaken by Obregón forces in the forests of Chiapas and killed by a pistol shot on June 9, 1924. He was only 44 years old.

Many of Alvarado’s reforms were reversed, only to be taken up by later leaders, who hailed him as an idealistic and honest revolutionary, a visionary hero.

This was Yucatán’s experience of the Mexican Revolution, then — the early “first spark,” years of inaction and opposition, and finally nonviolent change that became an example for the rest of the nation.

By Robert D. Temple

______________________________________

In Valladolid, a monument and garden in the ex-convent San Roque — now called Heroes’ Park — honor the martyrs of 1910. Every June hundreds of costumed citizens reenact the uprising, and official ceremonies commemorate the “first spark” of the Revolution.

Mérida honors Salvador Alvarado with a large monument to the west of the State Supreme Court building on the Avenida Jacinto Canek. His image appears prominently in the murals by Fernando Castro Pacheco in the Government Palace, and a large sports park bears his name.

Comments are closed.