Huffington Post contributor Rodrigo Aguilera writes that Mexico City’s new airport project is in many ways a microcosm of Mexico’s long-standing urbanistic failures and the politics behind them. It could also have serious environmental consequences that the government is playing down.

The collapse of oil prices and consequent loss of oil-related revenues have forced the government of Enrique Peña Nieto to considerably scale down its plans for grandiose infrastructure projects. However, one mega-project remains on drawing boards: a new international airport for Mexico City (referred to locally by its Spanish acronym, NAICM). As is the trend these days for any city with global aspirations, the futuristic design was drawn up a leading architect, in this case UK-based Norman Foster in partnership with Mexico’s own Fernando Romero. The new airport will occupy an area at least three times larger than the current airport (which has all but maxed out its potential for further expansion) and feature as many as six runways compared with just two in the current one.

Mexico City – an urban agglomeration of over 20 million and one of the top 20 cities in the world by GDP – desperately needs a new airport to satisfy its current and projected transport needs. In this sense, that the government fully intends to pursue its intention of building one is commendable, especially after the cancellation of its high-speed railway project (which had initially been awarded to a Chinese-led consortium only to see the tender retracted under suspicious circumstances). But the NAICM project is in many ways a microcosm of Mexico’s long-standing urbanistic failures and the politics behind them. It could also have serious environmental consequences that the government is playing down.

A Mesoamerican Venice

One of Diego Rivera’s most famous murals in Mexico City’s National Palace depicts an Aztec marketplace with an imposing background: the great city of Tenochtitlan as an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, crossed by canals and causeways. To say that at the time of the Spanish conquest Tenochtitlan was the Western Hemisphere’s Venice would be an understatement – Tenochtitlan was in fact 2-3 times larger than Venice despite the latter also being at the height of its glory. Little wonder that when Hernán Cortés described the Aztec capital in a letter to his sovereign, he warned that his account would “appear so wonderful as to be deemed scarcely worthy of credit; since even we who have seen these things with our own eyes, are yet so amazed as to be unable to comprehend their reality”.

Diego Rivera’s famous mural, La Gran Tenochtitlán, in the National Palace (Mexico City)[Image: Wikipedia Commons]

After the conquest, the Spanish would have to come to terms with the city’s one major urbanistic scourge: its vulnerability to flooding, which was exacerbated the destruction of the Aztecs’ delicate but effective regulation mechanisms. After catastrophic floods in 1555 and 1607 there began a centuries-long effort to dry out Lake Texcoco and by the time of independence most of the western half of the lake (the part directly under Mexico City) was gone. By the middle of the 20th century, the eastern and northern bits had shrunk into three smaller lakes and in the 1990s the middle lake – which retained the name of Lake Texcoco – had almost fully evaporated, leaving just a few wetlands and reservoirs. Nearly gone as well were Tenochtitlan’s waterways, which as early as the colonial period had been turned into sewage canals. Still, even up to the 1930s and 40s the city retained various usable canals (some dirty, some clean) but most were filled up to build the city’s urban expressway system – the inner ring, or Circuito Interior, still keeps the names of the rivers that one flowed beneath. That the few canals that remain in Xochimilco are a major tourist attraction points at the lost opportunity had more of them been preserved.

The fact that one of the world’s mega-cities is built on a lakebed has caused innumerable headaches over time, especially during the second half of the 20th century when the population skyrocketed and most of the area beneath Lake Texcoco was built up. The most obvious is that the city is slowly sinking due to the combination of its soft foundations and the slow drying up of its overused aquifer. The city is also made more vulnerable to earthquakes. The tragic September 1985 earthquake where over 10,000 Mexico City residents lost their lives is said to have been amplified by the weak subsoil, causing damage well in excess to what would be expected given the distance to the epicenter. The NAICM will be located in the most recently exposed area of the lakebed which presents an added challenge to the designers.

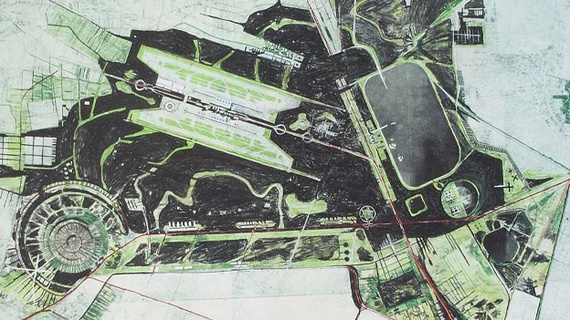

Compared to the original NAICM plan (red), the new location (blue) is squarely in the former lakebed. [Image: Rodrigo Aguilera]

How the previous airport plan failed

Barring the obvious geological issues, there is no more obvious place to build a massive new airport than in the vast emptiness of what was once Lake Texcoco in the Estado de México, the state that borders Mexico City. It is relatively close to the city which would mean that the cost of linking the airport to the city’s transportation system would be minimal. One of the sites that has for a long time been considered for an alternative airport, the municipality of Tizayuca, would be too far from the city (80 km) and require dedicated rail lines and shuttle services. Another benefit is the fact that the area is already owned by the federal government which will therefore avoid costly and politically troublesome land expropriations. In fact, the latter is the reason why the NAICM wasn’t built a decade earlier when the project was first launched under former president Vicente Fox (2000-06).

The failure of Vicente Fox’s airport plan is indicative of the Mexican government’s goldilocks attitude towards authority: too hard handed when it needn’t be, too indecisive when it needs to show its strength. Trouble began in October 2001 when the Fox administration chose the municipality of San Salvador Atenco as the site for the new airport. Atenco is mostly composed of ejidos – a collective rural landholding system established in the early 20th century but which following liberalization in the 1990s could be put up for sale or taken over through eminent domain. The government chose the latter route, offering the ejido owners a pittance in compensation and which resulted in protests, highway roadblocks, and marches in Mexico City featuring machete-wielding farmers from what now became known as the Frente Popular por la Defensa de la Tierra (FPDT, the Popular Front for Defence of the Land). In the face of this mini-insurrection, and even after its offer of increased compensation was rejected, the Fox administration capitulated, shelving the airport project the following year.

Fueled by their victory against the airport plans, the Atenco farmers remained politically active. In 2006, the FPDT went up in arms again after state police dispersed indigenous flower vendors from a Texcoco market. In the clashes that ensued, two FPDT members were killed and as many as 26 women suffered sexual assaults from the police. But despite reports from the National Human Rights Commission that the state police used excessive force, made over a hundred arbitrary arrests, and violated protesters’ human rights, no action was taken against them. The governor of the Estado de México who presided over this incident and who ordered the state police against the vendors and protesters was none other than Enrique Peña Nieto, who had been elected less than a year earlier.

A less than ideal location

If there is one better place to build the airport than on the dried up Lake Texcoco, it is in (or near) Atenco. The area benefits from being on more stable ground which would provide less of an engineering and environmental challenge, and it is not surrounded by major urban areas (the city of Texcoco is the closest and only has around 100,000 people). One of the original designs for the NAICM was for the airport to be located at the northeast edge of the lakebed, next to Atenco, but the location was later changed to the western edge, bordering the densely populated municipality of Ecatepec (with over 2 million people, it is Mexico’s largest).

Thankfully, the angle of the runways suggests that noise pollution will not be a major issue except to those neighborhoods nearest to the edge of the airport’s boundaries, but still, one wonders where the change in location is done out of political considerations than of actual practicality since the airport would now be located on far more fragile ground. In this sense, the shadow cast by the Fox administration’s failure a decade and a half ago along with the 2006 incident (which surely still lingers in Mr Peña Nieto’s mind) may be prompting the government to choose a sub-optimal location for the airport in order to preempt the threat of militant farmers spoiling what is Mexico’s biggest infrastructure project so far in the 21st century.

Needless to say, there has not been any consultation either with the affected neighborhoods of Ecatepec, which will soon have jet airliners taking off and landing just a few hundred meters away. That these neighborhoods are composed of mostly low income, working class families is telling of the little importance that is typically assigned in Mexico to those without the deep enough pockets to make their voices heard (or who aren’t willing to pick up machetes and march in Mexico City’s main square as the FPDT did back in 2001). The comparison with the long-running controversy over Heathrow’s third runway is illustrative of this, since many of the neighborhoods that would be affected by the expansion of London’s main airport are relatively affluent. Then again, the government knows well that when consultations do take place, the results are not always ideal. A poorly-conceived project (known as the Corredor Cultural Chapultepec) to revitalize the area around a major Mexico City avenue was recently shot down by the area’s middle- and upper-class residents.

What is also concerning is the lack of information on the different impacts that the airport will have on the region. Although an environmental impact study has been elaborated, neither cost-benefit nor technical feasibility studies have been made public. This lack of provision of information needed for civil society to make a judgment on the project’s benefits and risks is illustrative of a top-down approach that does not leave much room for the kind of policy debates that are taken as a given elsewhere (London’s Heathrow vs. Gatwick expansion plans for example).

Dreaming of lakes

In the long run, the NAICM in its current location all but destroys any possibility in the future to recover this last remnant of Lake Texcoco as a body of water. This has not just been a pipe dream for Tenochtitlan nostalgics but has been seriously considered by some of Mexico’s leading architects and urbanists. In the 1970s, the rector of the National Autonomous University (UNAM), Nabor Carrillo, led an effort to stop the still-existing lake from shrinking further through more efficient use of the aquifer, but the government never followed it through and the lake dried out two decades later. In the 1990s, renowned Mexican architects Teodoro Gonzalez de León and Alberto Kalach published a proposal known as Vuelta a la Ciudad Lacustre (“Return to the lacustrine city”) which envisaged a recovery of the Lake Texcoco area – even with a new airport designed around it, which proves that the two objectives are not mutually exclusive. More recently, architect Iñaki Echeverría proposed the Lake Texcoco as a major ecological conservation area composed of parks, leisure facilities and numerous smaller lakes.

Sketches from ‘Vuelta a la Ciudad Lacustre’. The need for a new airport was not ignored. [Image: CNN]

Unfortunately none of these plans have made so much of a dent in policy-making circles who likely see them as too expensive relative to their material or political benefit compared to a major infrastructure project designed by a globally-renowned “starchitect”. It also does not help that Mexican governments at all levels and of all parties have historically been lacking in imagination and competence when it comes to grand urbanistic thinking. Case in point: Morena leader Andres Manuel López Obrador didn’t miss the opportunity to gain some political leverage from the opposition to the new airport by making an entirely new “alternative airport” proposal that invites even more criticism than the NAICM plan.

But continued short-sightedness on the matter would be perilous. The main risk is that the massive and resource-intensive new airport ends up severely damaging the fragile hydrological balance that currently exists in the area, a risk that José Luis Luege Tamargo, a former head of Mexico’s National Water Commission (Conagua), recently described as “catastrophic” (Tamargo, by the way, picked Tizayuca as the ideal airport location). There has already been one ominous warning: heavy rains from tropical storm Arlene in 2011 forced authorities to flood the Texcoco lakebed so that the rising water levels would not spill over into the built-up areas. With these risks in mind, the benefits of restoring the dried up lakebed into a more natural environment of lakes and parkland makes far more sense, and would not be incompatible with building the much needed NAICM nearby, on firmer ground (i.e. Atenco or Tizayuca). And if the government cannot negotiate or deal with militant farmers for this to happen, then one must seriously question the capability of the Mexican government to get things done.

Thinking big

That the Peña Nieto administration is neither willing to listen to the airport’s critics, or to involve civil society in the debate is regrettable yet not surprising in a country where little effort is made to involve stakeholders in major policy decisions. But if the NAICM goes ahead in its current, less-than-ideal location, the government will be doing something worse: it’ll be shutting the door on the possibility of a much grander urban and environmental vision for one of Mexico City’s most economically-deprived and ecologically-vulnerable areas. If Peña Nieto cannot think big, he should at least not prevent his successors from doing so.

By Rodrigo Aguilera

Rodrigo Aguilera is a columnist for The Economist Intelligence Unit in Mexico City.

Source: huffingtonpost.com

Comments are closed.