February 29, 1933. After a long day of walking, Alfonso Villa Rojas arrived at the remote archeological site called Yaxuná. The 35-year-old schoolteacher had been working as an assistant on the Carnegie Institution’s restoration project at Chichén Itzá. Deeply interested in local oral traditions, Villa Rojas had heard tales about an actual paved roadway lost in the Yucatán thorn-forests. He received approval to spend a few weeks investigating.

Sketchy reports about the “white roads” of Yucatán existed from the earliest days of the Spanish invasion. The first historian of the Peninsula, Diego de Landa, mentioned “a very beautiful road” between Mérida and Izamal. Exploring near Valladolid in 1842, John Lloyd Stephens heard of an east-west-running stone road, apparently connecting ancient cities still unknown, although he was unable to reach it. By the 1930s, archeologists had discovered but scarcely explored the sites of Cobá and Yaxuná. The traces of ruined roadways they happened upon remained mysteries. Mayanists began using the term “sacbe,” plural “sacbeob,” for an elevated stone road or causeway, although the actual sounds in the Yucatec Mayan language are better represented as sak beh (white road), plural sak beho’ob.

Villa Rojas and his directors at the Chichén Itzá project agreed that Yaxuná, only about fifteen miles away, would be a good place to begin investigating the ancient road. He recruited a dozen local men to accompany him. One helped with making measurements, one looked after the two pack horses that carried supplies, and ten wielded machetes to clear a way through the dense forest and brush that entirely obscured their intended course. Provisions for the little expedition consisted of corn tortillas, pinole (roasted ground corn), and pozole (lye-soaked corn kernels), with ground squash seed and chile for seasonings.

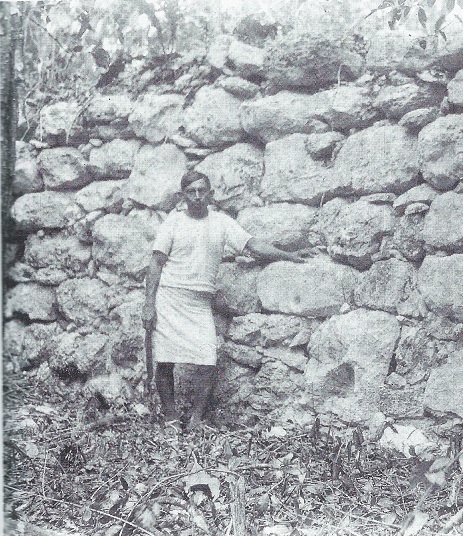

Villa Rojas found Yaxuná, a substantial city in ancient times, badly stone-robbed and in a state of extreme ruin, with only a few walls standing. He located a small mound where a sacbe seemed to begin, determined that its course headed a few degrees north of due east, and began measuring as he followed the clearing crew.

The explorers found themselves walking the ruins of a raised highway, thirty feet wide, straight and level, once smoothly paved. Not exactly an autopista, in truth, because there were no autos when it was built. Or wheels. But no one would build anything like it in Yucatán again for more than a thousand years.

Villa Rojas found that the sacbe ran eastward in perfectly straight segments, making several small changes in direction as it passed the sites of four or five ancient towns. It continued nearly level across natural rises and depressions, reaching an elevation of some eight feet as it crossed one low place at about its midpoint. It passed several adjacent structures, ramps, and platforms. The explorers were puzzled to find ramparts at many points, extending across the road and sometimes for a considerable distance on both sides. Twenty miles from Yaxuná, they were astonished to find a road roller, a polished stone cylinder twelve feet long and two feet in diameter, estimated to weigh five tons.

Stones taken to be distance markers appeared at regular intervals. Near the eastern end, Villa Rojas found several carved stones, each about 30 inches high and 20 inches wide. Although badly eroded, the inscriptions seemed to be similar, and what little could later be read includes numbers — probably dates — and one glyph interpreted as sak-bi-hi, the word “sacbe” in the Ch’olan language of Classic times.

After twenty days’ work, the explorers had mapped a ruined sixty-mile-long raised highway. They entered the ruins of the great city of Cobá, passed over a small pyramid, and reached its eastern terminus at a large plaza in front of the site’s largest pyramid, the eighty-foot-high Nohoch Mul.

In construction, the sacbe is like a long platform. Side retaining walls of roughly dressed stone enclose a roadbed filled with uncut boulders, leveled with gravel, and paved with liberal quantities of sascab — powdered limestone, a natural cement that hardens with water and pressure. The roadbed is higher in its center to allow drainage, and in some places the builders applied a finishing coat of smooth lime stucco. Lime cement, of which few traces remain, held the side walls together. Villa Rojas observed that many of the dressed stones had been taken away for use in more recent walls and buildings. He found evidence of quarries near the sacbe, doubtless the sources of construction material.

Consider the enormous amount of labor required to build and maintain the sacbe. The workers were probably corvée labor crews performing the short-term periodic services required of citizens, like faenas for members of an ejido in recent times. They dug the construction material with hafted stone tools, carried it in baskets, and burned limestone to make lime for cement and stucco.

We marvel at the size of the monumental pyramids at Maya sites, but the volume of stone in this sacbe is twenty-five times greater than that of the Castillo at Chichén Itzá.

Scholars have determined that constructing one cubic meter of stone and rubble masonry at the time required at least twelve man-days work, about equally divided between digging and transporting material, manufacturing and transporting lime, and doing the actual construction. (This does not count the time for planning, traveling, and clearing the land.) For this sacbe, the math works out to 500 men working for 50 years, a huge effort, but within the scope of the possible.

Coba Yaxuna sacbe at the point where it attains its maximum elevation, 8 feet (Photograph by Alfonso Villa Rojas, Carnegie Institution, 1933)

Why would anyone build an elevated causeway across Yucatán’s flat, waterless countryside? Without pack animals or wheeled vehicles, overland commerce in the Maya world traveled on the backs of individual humans. A simple, low-cost forest trail should be adequate, and these must have been common, though they left no traces. A sacbe would be better than a dirt trail in the rainy season, especially for a person carrying a heavy load, but still the value of the enormous investment required to build sacbeob seems questionable. How can we understand this?

None of the great Maya causeways had a single function. Roads reflect the values of society interacting with technology and environment. Practical communication and transportation were doubtless important but probably not their primary purpose. Accounts from the earliest colonial times stressed their significance for ceremonies — for processions and pilgrimages, for high-status visits between members of the nobility, for transferring ritual objects symbolizing the rotation of calendrical cycles. As in many cultures today, processional movement along roads was a powerful symbolic activity.

Further, the sacbeob were certainly political statements — symbols of the extent of a ruler’s power, prestige, and dominance. They were effective channels for moving armies. Built in stages and requiring little specialized skill, they were an ideal way for rulers to regularize demands for labor service. The collective effort was a way to strengthen social cohesion and the sense of belonging to a community. Monuments inspire group identity and pride.

Religious and political authority were not separate for the Maya, but the religious symbolism of roads was strong. Travelers burned copal incense at intervals along their way. Mythological forces flowed along symbolic roads believed to exist below the surface of the visible world and in the sky, like aerial umbilical cords. Roads allowed deities and ancestors to communicate with the living.

Language demonstrates the central image roads had for Maya people. Time was born and followed a road, the sun followed its road across the sky, life was a road, following one’s road meant fulfilling one’s duty and destiny. “To enter the road” was a metaphor for death. The usual friendly greeting even today — How are you? — translates as “How is your road?”

The earliest sacbeob date from about 300 BCE, and hundreds were built during the next twelve hundred years. Although some ninety sites have evidence of sacbeob, they were especially popular in Yucatán, and the sacbe connecting Yaxuná and Cobá is by far the longest one documented.

If we are to understand why these people decided to make such a large investment in building a great causeway, we need to look at what was happening in their lives at the time.

While we hear much about the “Classic Maya collapse” of the ninth century, the cities of Yucatán were flourishing at the time, far from collapse. Cobá had early ties with the great cities of the Petén — northern Guatemala — and represented an outpost of the Petén cultural tradition, which did fail. But the period between the years 800 and 1200 saw expansion and cultural vigor in the northern lowlands. At the height of its power around 800 CE, Cobá controlled all of the eastern Peninsula, and the city had an estimated population of 50,000 — larger than Shakespeare’s London, larger than any U.S. city before 1800. Cobá dominated trade on the Caribbean coast and was the most important center for redistribution of goods to the populous and growing interior cities of the Puuc region, such as Uxmal and Oxkintok.

Yaxuná was a smaller but very ancient city that profited and suffered from its location on an open but tense border between more powerful regimes. A trade crossroad for goods from the Caribbean, salt from the north coast, and ceramics from the interior, the city attracted political interest from powerful neighbors and experienced violent episodes.

Cobá, in an expansionist phase and in control of Yaxuná, looked with concern at the growing Puuc cities to the west. Of even more concern was a new rival that had appeared in the north — the Itzá. A coastal trading people strongly influenced by the culture of central Mexico, the Itzaes began a program of conquest around the year 700, moving inland from their principal port, Isla Cerritos. They conquered Izamal and advanced toward the south, where they encountered resistance from Cobá and the Puuc entities. In about 800, they began building their new capital, Chichén Itzá, within fifteen miles of Yaxuná.

So it seems pretty clear that imperial Cobá built the long sacbe as a symbol of control and as a military highway. It was a political monument. They wanted to stake an unmistakable claim to their western boundary and be able to mobilize forces to defend it. Maybe they were deliberately challenging their rival.

Yaxuná had been a town in decline, but construction of the sacbe, between 750 and 850, gave it new importance. Archeological evidence shows that a population boom and building frenzy ensued. The new prosperity did not last long.

Caught between great powers engaged in a long struggle for control, Yaxuná became the site of confrontation. Images of warriors dominating prisoners appear in carvings, the acropolis was fortified, and roughly constructed city walls went up. The final attack came on a day between 900 and 950. Stone blocks prepared for construction but not put in place give evidence of hasty evacuation; one can imagine the mason dropping his tools and running. The great road to Cobá could not save Yaxuná. The victorious Itzaes sacked, desecrated, and ritually destroyed the city, which never recovered.

It appears that the Itzaes then moved directly against Cobá itself, using the fine sacbe to attack its builders. This phase of the war explains the ramparts Villa Lobos found thrown up across the road. We do not know whether Cobá actually fell to the Itzaes. It was not abandoned, but went into a slow decline. Loss of Yaxuná cut off its commerce with central Yucatán. The Itzaes concentrated attention on taking over the maritime trade routes, not occupying interior territory they would have to defend. They dominated the region until they were conquered by Mayapán and its allies in about 1250.

Although we can perhaps understand the purposes of the great Yaxuná-Cobá sacbe, intriguing mysteries remain. What use did travelers make of the platforms and structures along its course? Were they religious shrines and altars? Resting places, perhaps lodgings run by innkeepers? Toll-collection or customs stations? What messages did the texts on the distance markers have for us? We can only imagine the glories of the elegant processions, the hurrying messengers, and the fierce warriors that passed along this road.

Although all the ancient sacbeob eventually fell into disuse and ruin, they never vanished from the land or from memory. The Yaxuná-Cobá sacbe was a boundary marker between chiefdoms into colonial times. When Governor Lucas de Gálvez undertook a road-building program in 1790, he had a Spanish road built atop the Maya sacbe between Mérida and Izamal. John Lloyd Stephens reported that some Maya people said a short ritual prayer when crossing a sacbe, even though it had been overgrown with jungle for centuries.

Alfonso Villa Rojas, first explorer of the longest sacbe, went on to a brilliant career, earning international recognition as the preeminent Mexican ethnographer of the century.

For us, as for our ancestors fifty generations ago, no engineering structure but a road so mirrors human existence and overcomes distance to bring us together.

by Robert D. Temple

____________________________

A modern road, Highway 295, crosses the Yaxuná-Cobá sacbe 13.6 miles south of Valladolid, 1.2 miles south of Tixcacalcupul. There is a small pull-off and a sign, “Camino Maya,” but the ancient roadway is usually obscured by brush and weeds and difficult to see.

At the western end, the site of Yaxuná has had some clearing and consolidation but little restoration and no interpretive signs. It will probably be difficult for the non-expert to find the sacbe.

The best place to see what the Yaxuná-Cobá sacbe was like is at its eastern end, within the excellent site of Cobá, where several sacbeob are cleared and easily visible. The visitor can walk partially restored roadway for some hundreds of yards.

Robert D. Temple, PhD, is the author of the award-winning book Edge Effects and numerous magazine articles, mostly dealing with matters of local history. He lives in Yucatán, Ohio, and Virginia. This is part of the ‘Surprising History in Yucatán’ series, which has appeared in The Yucatan Times since January 2014.