The Maya civilization flourished more than 1,000 years ago, but modern technology is only now revealing the secrets of this ancient Mexican and Central American culture—and it’s happening at an unprecedented pace. A recent spate of discoveries is transforming the field of Maya archaeology, as researchers discover new ways to identify and investigate ancient ruins.

In 2018, archaeologists in Guatemala announced the discovery of thousands of unknown Maya structures, hidden in plain site beneath overgrown jungle greenery. But it wasn’t a bushwhacking, Indiana Jones type who found them. Instead, the ancient ruins were identified remotely, thanks to aircraft from the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping that were equipped with high-tech Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) mapping tools.

Using laser pulses tied to a GPS system, LiDAR makes topographical readings and creates three-dimensional maps of the earth’s surface. In an instant, LiDAR can survey a wide geographic area that would take years to map on foot.

“LiDAR is showing us things that we never would have been able to see with 100 years of research—and we have 100 years of research under our belts already, so it’s not like that’s hyperbole,” archaeologist Marcello Canuto told artnet News. An anthropology professor and the director of the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University in New Orleans, Canuto is on the committee that oversaw the landmark LiDAR initiative in Guatemala, funded in 2016 by Pacunam, or Patrimonio Cultural y Natural Maya, Guatemala’s Maya heritage foundation.

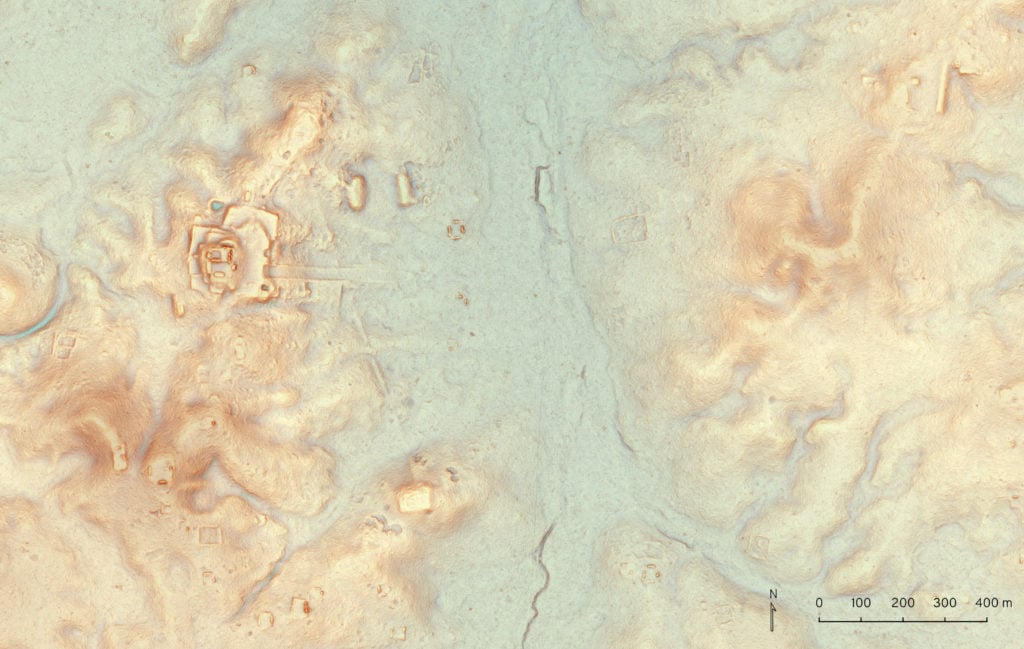

A newly discovered ancient Maya site north of Tikal as detected by LiDAR. Image courtesy of Luke Auld/Thomas Garrison/Pacunam.

A “Paradigm-Shifting” Technology

Archaeologists have long been aware of the tremendous potential of LiDAR. Back in 2009, the technology was used to great effect in Belize, where it scanned an 80-square-mile region at the archaeological site of Caracol.

“We started trying to get LiDAR in 2005. Everybody told us we were nuts, that it wouldn’t work,” Arlen Chase, the co-director of the Caracol site, told artnet News.

Now a professor of anthropology at Pomona College in Claremont, California, Chase was convinced that LiDAR was the answer to archaeologists’ prayers. But when the results of the scans finally came back, “I was completely stunned,” he said. “It worked far beyond our wildest dreams.”

For years the Caracol team had been aware that they were were working on a site that stretched deep into the jungle, but to prove as much was another matter. “Caracol is over 200 square kilometers,” said Chase. “Trying to convince our colleagues of that in 2009 was impossible without the LiDAR.”

The mapping project showed just how big the city truly was, revealing causeways and other structures previously hidden beneath the jungle. Caracol was a large, continuous settlement that showed that the Maya had dramatically transformed their landscape.

“LiDAR is paradigm-shifting,” Chase said. “It’s effectively changing our entire view of the ancient Maya.” Each time it covers a new area, “you start to see different things.”

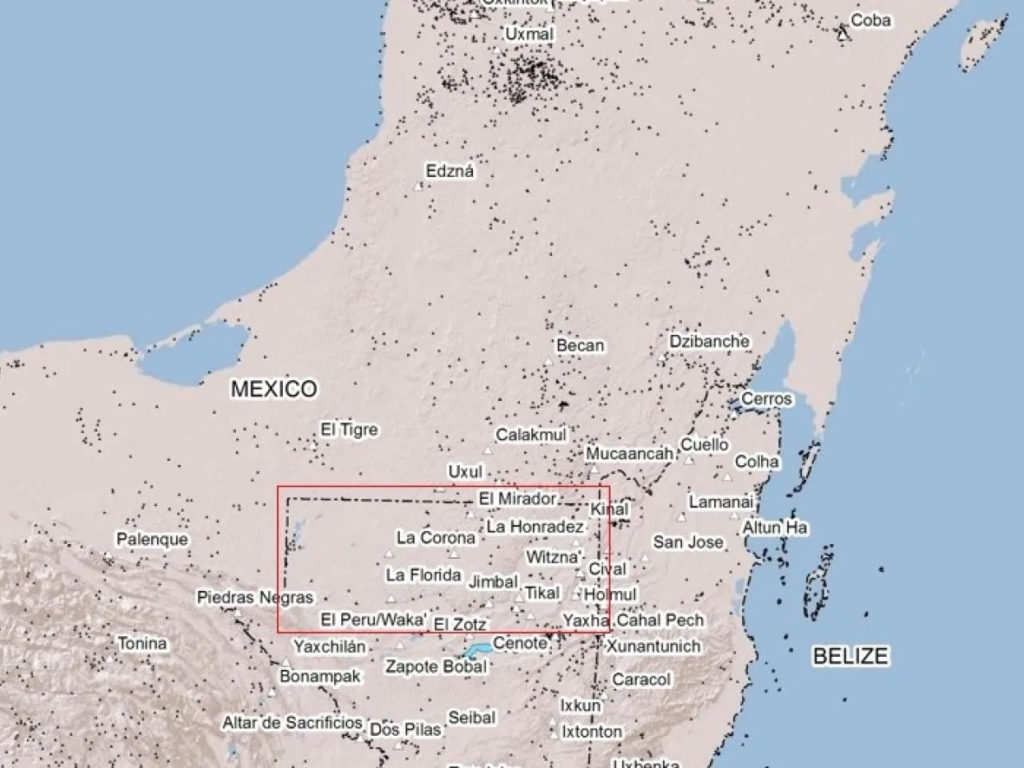

Over the last decade, many archaeology projects in the region have begun using LiDAR, revealing more and more about this lost civilization. But the Pacunam project was unprecedented. No one had ever scanned such a large geographic region with LiDAR at one time.

61,000 Maya Structures in One Day

“As an archaeology remote sensing expert, I have been using satellite imagery for years trying to locate sites under the dense jungle canopy,” Francisco Estrada-Belli, also a professor of anthropology at Tulane University, told artnet News in an email. “When I learned about LiDAR, I was skeptical initially because it looked like it could only map small areas. Then we learned that with the right amount of money—many times more than what we can raise for a single-season expedition—we might map a very large area in a matter of days.”

Canuto and Estrada-Belli were among the lead researchers on the groundbreaking LiDAR project launched by Pacunam. As a Maya cultural heritage foundation that works with a large number of Guatemalan archaeological sites, Pacunam was the perfect organization to oversee a project of this magnitude.

“Most researchers are interested in their own particular site and the area around it, and LiDAR is pretty expensive,” explained Canuto. “For an individual researcher to say, ‘Hey, give me a half-million dollars or a million dollars to cover this whole massive area over which I do not have any permit to do any research,’ would not have worked. Pacunam was the perfect entity to be able do LiDAR in these different regions and then coordinate the results.”

Based on the results at Caracol, and other sites surveyed with LiDAR, archaeologists were expecting to be able to identify new architecture elements built by the Maya. “The technology is fabulous,” said Chase. “We knew they were going to find all kinds of interesting stuff.” But no one could have predicted just how extensive the findings would be.

The Pacunam LiDAR Initiative scanned the Maya Biosphere Reserve in northern Guatemala, finding tens of thousands of previously unknown ancient structures. Image courtesy of Francisco Estrada-Belli/Pacunam.

Remarkably, a digital landscape generated of an 810-square-mile area of the Maya Biosphere Reserve in Petén, Guatemala, revealed no less than 61,000 unidentified ancient Maya structures that were invisible to the naked eye because of overgrown vegetation. What experts had mistaken for unusable swampland, for instance, had actually been farmland, crisscrossed with canals.

Seeing so many previously unknown roads, irrigation systems, defense fortifications, and other buildings, scholars started reevaluating their estimates as to how many people lived in the region—instead of five million, Petén may have been home to a population of up to 10 or even 15 million people.

“We knew the Maya were a complex and sophisticated civilization,” said Estrada-Belli, but “the size, density, and complexity of cities and the amount of landscape infrastructure the Maya built was just astonishing.”

The day the LiDAR data arrived, Canuto and Estrada-Belli had plans to attend a conference. Instead, they couldn’t tear themselves away from the computer, waiting with bated breath as a team at the University of Houston uploaded files with two gigabytes of data to a shared cloud.

“It was just one surprise after another,” Canuto recalled. “We couldn’t get enough of it.”

“We started looking around at 2 p.m. By 8 p.m., there were maybe 15 or 20 students in our lab, staring at these images we were getting,” he added. “I remember telling the students, ‘Remember this day, because this is the day that lowland Maya archaeology really changed.’”

CLICK HERE FOR FULL ARTICLE ON news.artnet.com