Scientists from UNAM’s Geology and Anthropological Research Institutes, together with members of INAH, participated in the discovery of the oldest remains of bonfires used by the first inhabitants of America.

TULUM Quintana Roo (INAH/UNAM) – Scientists from UNAM participated in the discovery of the oldest traces of bonfires used by the first inhabitants of America, in the flooded cave Aktun-Ha, near Tulum, Quintana Roo. The fires are 10,500 years old, placed in strategic locations to obtain illumination, as a guide to return to the surface.

“They are evidence of the survival strategies, organizational and planning capacities, as well as the symbolic and ritual meaning of the caves for the first inhabitants,” said Alejandro Terrazas Mata, of UNAM’s Institute of Anthropological Research (IIA).

The research carried out at the Institute of Geology (IGL), with the support of the IIA, and in conjunction with members of the INAH, was published a few days ago in the international journal Geoarchaeology, and confirms the hypothesis that these are vestiges of the use of fire by the first inhabitants of the Yucatan Peninsula.

Aktun-Ha is a flooded cave -cenote-, in total darkness, that 15 thousand years ago, when the sea level was 150 meters lower than the present one, was dry. The first settlers were able to use it as a dwelling place or to perform rituals.

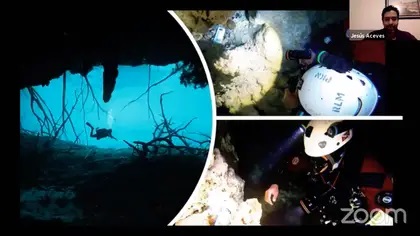

In that unique site, 30 meters underwater and about 100 meters from the entrance, in the hall or gallery known as the Chamber of the Ancestors, archaeologists from the Underwater Archaeology Department of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) found 15 accumulations of coal and fires that were carefully documented, measured and sampled.

The university student explained that at least 13,000 years ago, populations arrived from central Mexico to the territory now occupied by Quintana Roo. In the cave systems near Tulum, eight individuals (skeletons) have been found “that we have studied, and we see that the shape of the skull does not resemble that of its contemporaries.

Their ancestors came from colder climates, in the north of the continent. “Their skulls were longer and narrower, very different from those of today’s indigenous populations, which are more extensive in the face. Besides, the archaeologist discovered, their weight and height were less. They were smaller and lighter than other populations of hunters and gatherers.

It is known that the prehistoric population of Quintana Roo did not inhabit the caves, but used them as funerary and ritual contexts. “They possibly entered to deposit the bodies of important people for the community, since they were considered sacred sites,” Terrazas said.

(Photo: Courtesy of UNAM)

That population lasted more than four thousand years, and during that time, it was different from the rest of the groups in the continent. That is, the skeletons of Quintana Roo have variants in comparison to those found in the north or south of America, “undoubtedly because of the geographic isolation in which they lived, probably in a jungle environment, with a humid climate similar to today.

However, he acknowledged that more evidence is needed because, despite 20 years of research, no cultural evidence has been found associated with the skeletons, such as stone tools or offerings. It is unknown what their technology or cultural adaptation was like, “but the study of the fires gives an idea of their strategy for going into caves and depositing the dead or carrying out any other ritual activity.

Solleiro explained that the Aktun-Ha geological system is located in the corridor from Playa del Carmen to Tulum, where a group of caves and fractures are connected. The entrance to the cave is in the cenote. To enter the Chamber of Ancestors, you need specialized diving. There, no other archaeological evidence was found than possible bonfires and remains of rocks that seemed to be burned.

“It had to be verified that those remains were coal and if the evidence was a product of human activity or had been transported through surface and underground waters to the site. For this, a three-phase methodology was implemented: experimental, where rocks were burned to determine their physical changes by fire; field, with the collection of samples of coals and burned rocks; and laboratory for the analysis and dating of the coals, among other aspects”.

(Photo: Courtesy of UNAM)

It was found, among other results, that the “age” of the fires is 10,500 years and that the coals were produced in situ; the fire originated right there, and the temperatures reached in those fires were between 200 and 600 degrees Celsius.

Possibly some of the fires were used for food preparation or heating, and those found in a kind of niches could have served to illuminate the place, concluded Solleiro.

The research work was financed and collaborated by the General Directorate of Academic Personnel Affairs of the UNAM, the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, and the National Geographic Society.