The DEA’s assertion about the alleged communications recordings in its possession that confirm the crimes committed by Salvador Cienfuegos puts the finger on the suspicion that the U.S. maintains a spy program in Mexico.

MEXICO CITY (Milenio News) – The revelation that the U.S. government has taped communications to former Secretary of National Defense Salvador Cienfuegos has opened a debate among Mexican security officials, former U.S. agents, and academics as to whether the government of Donald Trump maintains a spying program on Mexican territory.

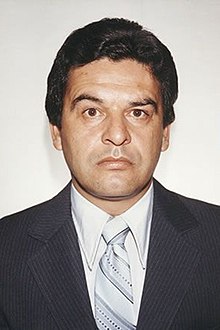

Secretary of Defense General Salvador Cienfuegos (Photo: Google)

In light of various revelations regarding taped communications to high-level officials such as Cienfuegos and former Secretary of Public Security, Genaro Garcia Luna, the question that remains on the table is clear: Where did the recordings that Washington claims to have come from and how did the DEA obtain these communications?

So far, the U.S. government claims to have tapped calls from at least three Mexican public servants to whom communications have been intercepted, particularly in instant messages of Salvador Cienfuegos, Genaro García Luna, and Iván Reyes Arzate, which they believed were encrypted on their smartphones.

Genaro García Luna

In a review made of the information made known by the U.S.U.S. authorities in the three cases, all of them present as evidence conversations that, presumably, the officials had directly with drug lords, even while in office. Either in a call or through messages, but no further details are given about which phones were tapped to obtain such evidence.

Cienfuegos was Secretary of Defense during the six-year term of Enrique Peña Nieto. “From what I’m seeing, it means that Americans are spying on Mexico,” a former top national security official told MILENIO.

“We never spy on Mexican territory. These are calls that are made in the United States,” said Mike Vigil, former head of international operations of the DEA. But there is no doubt that the United States hears and reads the messages of Mexican politicians or officials accused of having criminal ties: indictment 19-366 (CBA) filed against General Cienfuegos, who was secretary of defense during the six-year term of Enrique Peña Nieto, proves it.

To a large extent, it is based on the interception of “thousands of BlackBerry messages,” including “numerous direct communications” between the general and a leader of the H-2 Cartel, whom he does not mention by name. Still, presumably, it would be the capo Juan Francisco Patrón Sánchez, who was shot down by the Navy in 2017.

Regarding García Luna, the prosecutors in charge of his case have reiterated that they have “voluminous” evidence against him. There would be calls and voice recordings of tapped devices, which prove that he is part of the Sinaloa Cartel structure.

Genaro García Luna was Secretary of Public Security in the government of Felipe Calderón. Reyes Arzate was designated as the liaison between the Federal Police and the DEA. Prosecutor Ryan Harris has said that there are “more than two thousand recordings on a BlackBerry device that add up to thousands of pages,” which would prove his direct contact with capos of the Beltrán Leyva and El Seguimiento 39 who, allegedly, received millionaire bribes.

Some former security officials consulted by MILENIO, in exchange for maintaining their anonymity, “we’re concerned that, from the United States, the work of senior security institution officials is being spied on.”

They also warned that it is illegal for foreign agencies to carry out wiretapping on Mexican territory and pointed out that, in a hypothetical scenario, in the three cases mentioned, it would be the Mexican intelligence agencies that would have carried out the wiretapping.

If the recordings and message interceptions to Cienfuegos, García Luna, and Reyes Arzate were made by the DEA or any other U.S. security agency to devices in Mexico, the officials consulted were categorical: it would be a flagrant violation of national sovereignty.

In this regard, the DEA’s former head of international operations reiterated that the agency does not carry out interceptions in Mexico, much less, to public officials. “What happens is that we have operations in the United States where we hear drug traffickers referring to Mexican officials,” he explained.

Wiretapping, even in the United States, is considered so intrusive that federal law requires the approval of a senior Department of Justice official before agents. In this case, the DEA can ask permission from a federal court to conduct one.

The academic from the Colegio de la Frontera Norte, José María Ramos, recalled that wiretaps are part of the DEA’s modus operandi for investigating high profile cases such as that of General Cienfuegos. Regardless of whether his defense can prove an irregularity in how they were obtained, in reality, with a view to the budget, they will position the agency’s leadership in his country as the main counter-narcotics fighter.

It is not the first time that suspicions arise regarding the U.S. security agencies tapping the phones of high ranking Mexican public officials, who are accused of having dealt with the drug trade. In the ’80s, suspicions strained relations between both countries, after the alleged wiretapping of some Mexican officials by the CIA was revealed, as detailed in a declassified document from that intelligence agency.

During the Reagan administration, almost 40 years ago, the United States authorized as a national security measure to use military surveillance and intelligence to fight against drugs.

According to a declassified CIA report in November 1986, The San Diego Union revealed the agency’s alleged contribution to Reagan’s anti-drug crusade by spying on the phone conversations of several Mexican officials suspected of being part of the old drug cartels.

The wiretaps were allegedly carried out without giving notice to the Mexican government in charge of Miguel de la Madrid. For fear of leaking details that would put the operation at risk, reads the declassified CIA report.

Special Agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena

According to the report, which includes a multitude of journalistic articles on the subject, the wiretapping was carried out after the distrust that arose in the U.S. justice system towards Mexico, following the assassination of Special Agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena a year earlier, in circumstances that remain unclear three decades later.

The official story maintains that it was members of the Guadalajara Cartel who planned and carried out the kidnapping, torture, and murder of the special agent together with a Mexican pilot. From the beginning, it has been said, as an open secret, the alleged participation of high-level Mexican officials.

After the San Diego Union’s revelation, a spokesman for the spy agency, George Lauder, denied that Mexican officials were being watched because of their ties to drug traffickers, according to the press at the time.

At the same time, an anonymous source in the intelligence community accepted that the CIA provided the DEA and the Justice Department with information related to the fight against drugs that they could not obtain on their own, for example, secret telephone tapping, the declassified document details.