The city of Tikal purified one of its reservoirs with technology comparable to modern systems.

TIKAL Guatemala – (Livia Gershon/SMITHSONIANMAG.COM) – More than 2,000 years ago, the Maya built a complex water filtration system out of materials collected miles away. Now, reports Michelle Starr for Science Alert, researchers conducting excavations at the ancient city of Tikal in northern Guatemala have discovered traces of this millennia-old engineering marvel.

As detailed in the journal Scientific Reports, the study’s authors found that the Maya built the Corriental reservoir filtration system as early as 2,185 years ago, not long after settlement of Tikal began around 300 B.C.

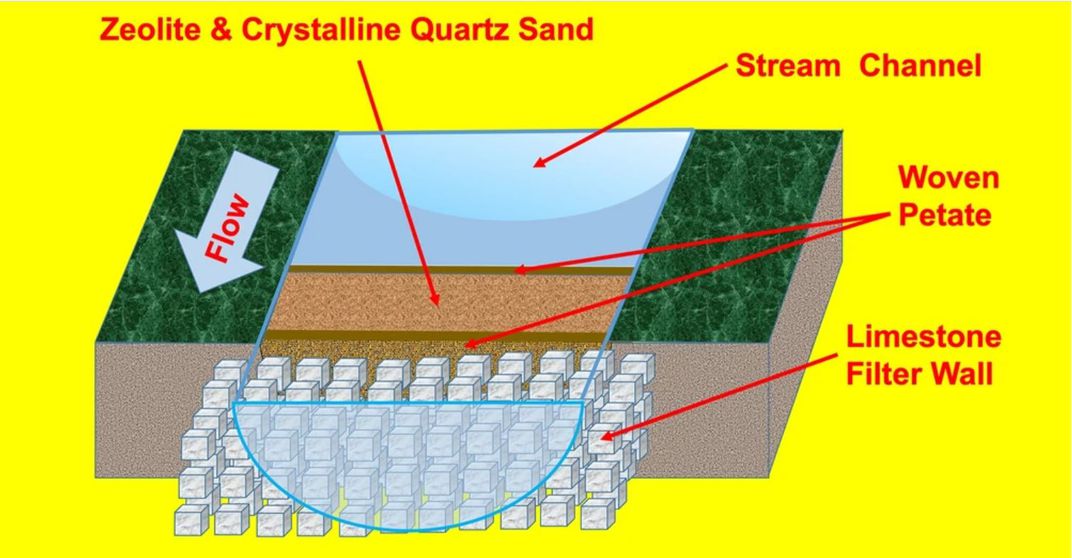

The system—which relied on crystalline quartz and zeolite, a compound of silicon and aluminum, to create what the researchers call a “molecular sieve” capable of removing harmful microbes, heavy metals and other pollutants—remained in use until the city’s abandonment around 1100. Today, the same minerals are used in modern water filtration systems.

“What’s interesting is this system would still be effective today and the Maya discovered it more than 2,000 years ago,” says lead author Kenneth Barnett Tankersley, an archaeologist at the University of Cincinnati, in a statement.

According to Science Alert, archaeologists previously thought that the first use of zeolite for water filtration dated to the early 20th century. Researchers have documented other types of water systems—including ones centered on sand, gravel, plants and cloth—used in Egypt, Greece and South Asia as early as the 15th century B.C.

“A lot of people look at Native Americans in the Western Hemisphere as not having the same engineering or technological muscle of places like Greece, Rome, India or China,” says Tankersley. “But when it comes to water management, the Maya were millennia ahead.”

Per the statement, water quality would have been a major concern for the ancient Maya, as Tikal and other cities across the empire were built on porous limestone that left little water available during seasonal droughts. Without a purification system, drinking from the Corriental reservoir would have made people sick due to the presence of cyanobacteria and similarly toxic substances.

The Tikal filtration system used quartz and zeolite to remove both heavy metals and biological contaminants. (Kenneth Barnett Tankersley / University of Cincinnati)

Members of the research team previously found that other reservoirs in the area were polluted with mercury, possibly from pigment the Maya used on walls and in burials. As Kiona N. Smith reported for Ars Technica in June, drinking and cooking water for Tikal’s elite appear to have come from two sources that contained high levels of mercury: the Palace and Temple Reservoirs. Comparatively, the new research shows that Corriental was free of contamination.

The researchers write that the Maya probably found the quartz and zeolite about 18 miles northeast of the city, around the Bajo de Azúcar, where the materials naturally purified the water.

“It was probably through very clever empirical observation that the ancient Maya saw this particular material was associated with clean water and made some effort to carry it back,” says co-author Nicholas P. Dunning, a geographer at the University of Cincinnati, in the statement. “They had settling tanks where the water would be flowing toward the reservoir before entering the reservoir. The water probably looked cleaner and probably tasted better, too.”

Tikal, known as Yax Mutal to its ancient inhabitants, consisted of more than 3,000 structures. At its height in 750, it was home to at least 60,000 people, as David Roberts reported for Smithsonian magazine in 2005. After its abandonment 900 years ago, much of the city was lost until the late 20th century, when Guatemalan archaeologists excavated what’s known as the Lost World, a complex of pyramids and buildings that had long been hidden in the jungle.

Researchers have found written records that provide a complete chronology of the Tikal’s rulers over an 800-year period. In 1979, Unesco designated Tikal National Park as a World Heritage site, citing its well-preserved structures and art, which attest to the development of Maya culture and science.

The newly discovered filtration system adds to researchers’ understanding of Maya scientific achievements. Next, says Tankersley, he wants to look for other Maya sites that may have used the same water purification technology.

Read the original article here.

Livia Gershon for SMITHSONIANMAG.COM

—

Livia Gershon is a freelance journalist based in New Hampshire. She has written for JSTOR Daily, the Daily Beast, the Boston Globe, HuffPost, and Vice, among others.

Read more from this author | Follow @LiviaGershon