Few archaeological discoveries have caused as much interest as that of the polychrome bust of Nefertiti.

Mèrida, Yucatàn, (April 29, 2021).- Its exhibition for the first time in Berlin in 1924 made this queen of Egypt world-famous, of whose life there was hardly any data at that time. The main wife of Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, better known as Akhenaten, Nefertiti was the protagonist of one of the most exciting periods in the history of the Nile country.

The work shows, with overwhelming simplicity, a distinguished and serene woman dressed in royal insignia. Its discoverer, Ludwig Borchardt, said: ‘All description is useless, you have to see it!’ The world fell for her charms and she immediately became an icon of beauty. Thus, the meaning of her name was honored, ‘the beauty has come’. But experts also surrendered to the artist, rescued from the past in the face of the anonymity that characterizes Egyptian works.

DISCOVERY OF THE BUST OF NEFERTITI

An Egyptian workman discovered the bust on the afternoon of December 6, 1912, during the excavations of the German Society for Oriental Studies at Tell el-Amarna. The site, one of the largest in Egypt, hides the city of Ajetatón, founded by Akhenaten as the new capital of the country and seat of the new national God, Aten.

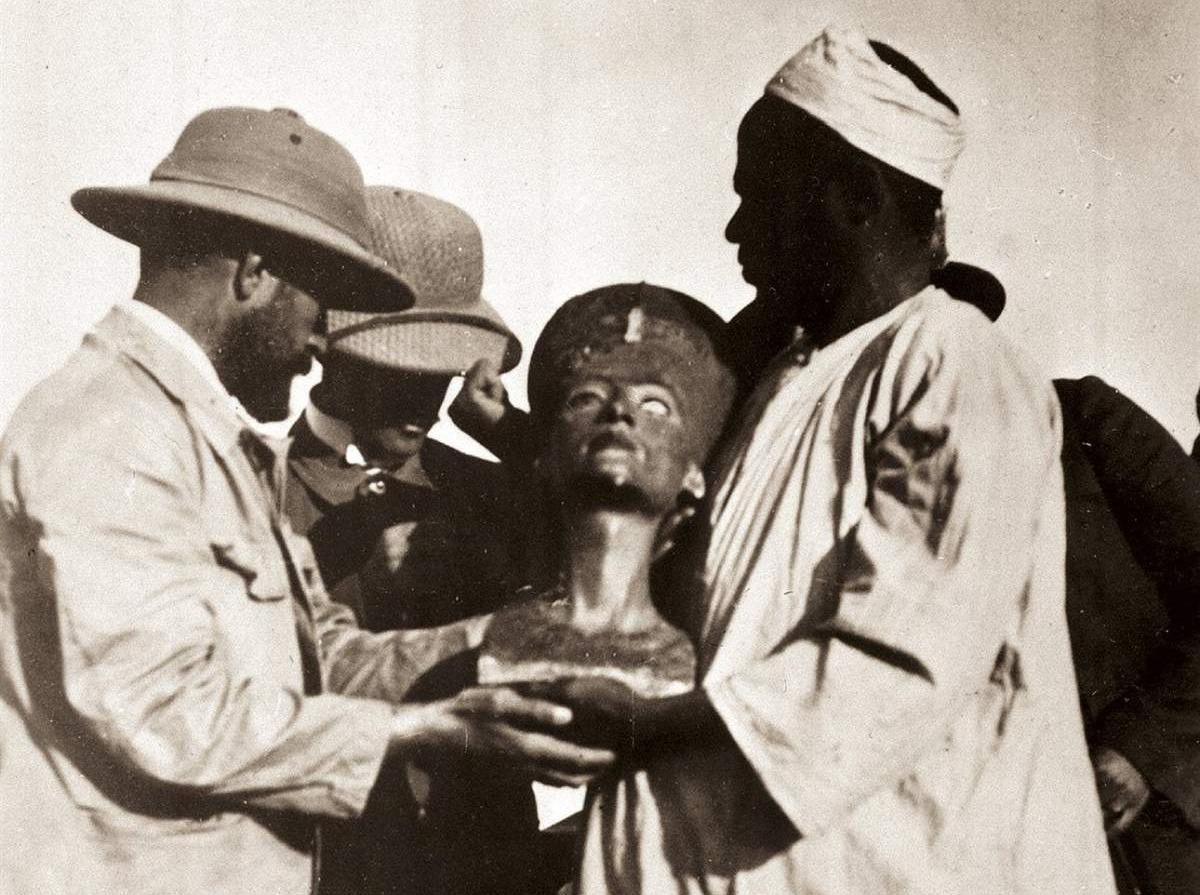

The head of the German mission was archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, who led the excavation rigorously. The bust came to light in the southern neighborhood, in one of the artist’s workshops that existed in the city. Its owner was the ‘head of the works, the sculptor, Tutmés’, titles that indicate that he was in charge of this guild.

The effigy of Nefertiti was found in a small warehouse. More than fifty works were scattered there, most of them cast in plaster of heads along with busts and parts of unfinished statues. At the time of the discovery, the remains of the shelf in which it had been placed could be distinguished next to the bust of the queen. The most surprising thing is that, once the sculptor finished saving the works, he had the door sealed.

A MASTERPIECE

The presence of the bust of Nefertiti in the workshop makes sense if you consider that it was not conceived to be exhibited in any temple, but to be used as a sculptor’s model. In fact, the bust never existed as a genre in pharaonic art.

It seems that the main purpose of the work was to show the inlay technique of the eyes. The right one is formed by a rock crystal, on the back of which black pigment was applied to represent the pupil and the iris, which was glued to the basin with wax. But the left one was left empty.

It has been said that it came off when the sculpture fell from the shelf, although Borchardt himself searched for it without success. Or even that it was due to an eye disease of the queen or a fit of jealousy from Tutmés himself. The truth is that it was never inserted. The latest analyzes have shown that there are no remains of any type of glue in the left basin.

HOW TO KNOW WHAT SHE IS?

In the workshop, many models of heads of different members of the royal family and the court were found. And although the bust of Nefertiti does not contain any inscriptions, her identification is indisputable. The greatest proof is the presence of the tall blue crown with which it was used to represent it.

The softness of his features, compared to the more exaggerated forms that characterize Amarnian art, is a criterion used by specialists to date the work. For some, the bust was executed when the court still resided in Thebes; For others, it represents the new official face of the queen some time after the transfer, perhaps around the year 8 of Akhenaten’s reign. The architect most likely was Tutmés, who endowed what was a study with masterful perfection.

DESTINATION BERLIN

At the end of the campaign, the objects were officially distributed, which was then 50%. It was carried out between the archaeological team in question and the representative of the Egyptian Antiquities Service (at that time headed by a Frenchman) on behalf of the Cairo Museum. That is to say, on the one hand, Borchardt and on the other, the epigraphist and papyrologist Gustave Lefebvre.

The meeting took place at the Cairo museum on January 20, 1913. Lefebvre chose first and opted for a painted relief fragment representing the royal family. There has been much speculation about the reasons for its choice and even if the piece could somehow be disguised, thus diverting the attention of the French, little experienced in these matters.

Be that as it may, the bust traveled to Berlin. But it was not delivered directly to the archaeological museum (which, a few months later, did exhibit the rest of the objects brought from Tell el-Amarna), but to the patron who had financed Borchardt’s excavation, James Simon. Only when he bequeathed his private collection to the museum, in 1920, was the bust included in the national assets. However, it took several years for it to be publicly displayed. Some point to disagreements between the museum director and Borchardt himself.

Egypt then claimed the bust and called his departure from the country illegal, because it was not consciously authorized. Relations with Germany cooled to the point that the Egyptians banned any German excavation. As for Borchardt, his work at Tell el-Amarna had ended at the outbreak of the First World War.

OBJECT OF DESIRE

From this moment on, the new director of the Antiquities Service, Pierre Lacau, started some negotiations for a possible return. The controversy ended up becoming a matter of State. In 1929 the possibility of exchanging works was raised without success: the bust for two important sculptures. Four years later, coinciding with the birthday of Egyptian King Fuad I, a return was attempted again years later, but Adolph Hitler overruled it.

Nefertiti did not leave the country, but her museum display case temporarily, because of the Second World War. For several weeks she was hidden in a mine in Thuringia, 350 km southwest of Berlin. In April 1945, the American army took over and freed the queen, and in 1953 returned her to West Germany, which initiated its own dispute with her eastern counterpart.

Egypt has not waived its demand. The archaeologist Zahi Hawass, who requested his loan in vain during his time as Egypt’s Minister of Antiquities, continues to demand the return of the piece. And the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, owner of the bust, continues to insist on the legality of the acquisition.