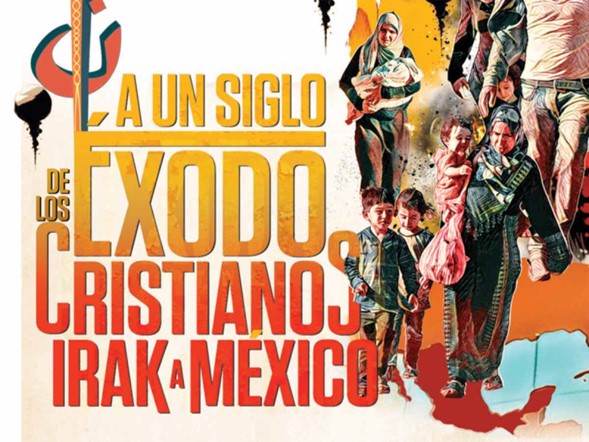

Between the end of the 19th century and the first 30 years of the 20th century, about 200 Iraqi Christians of the Chaldean rite migrated from Telqef and Mosul, Iraq, to Mexico, fleeing from wars, extremism and poverty.

They understood that Mexico was the country that welcomed migrants from the Middle East and allowed them to form families with the inhabitants of this nation.

In an interview with Excélsior, radiologist physician and writer Ulises Casab Rueda, author of the book Los Cristianos de Iraq en México, describes how this migration went, and how they settled mainly in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Oaxaca.

“Jajju Hajji is the first Iraqi at this time to arrive in Ixtepec, Oaxaca, then this man sends a letter and goes back to Iraq and charms many, mostly young people and they come in 1914 to Mexico,” he recounted.

“Among the young Iraqis who come to Mexico was my father, Tobias Casab Odish; he was 14 years old. My father works, marries my mother, Julia Rueda, a green-eyed Zapotec woman of Spanish heritage, and they have their children,” he recalled.

On his first trip to Mexico, Tobias Casab made his fortune and returned to Iraq for a period of three years and eleven months, and it was in that Arab country where Ulysses Casab was born.

Iraq gained independence in 1930, but in 1936, prior to the Second World War and with the emergence of guerrillas, Mr. Casab Odish decided to return to Mexico for the second time with his wife and their first children, among them Ulises, who was only one year and two months old.

Ulises Casab recounted that when he was a baby, with his father living near Baghdad, he decided to travel again to Mexico, a trip that would have no return.

“In Iraq, my father was the owner of the only wheat mill in his village, a poor village, he gathered all his children and my mother and returned to Mexico, again to the same place where he had made his fortune, Ixtepec,” the historian told this newspaper.

“Of my siblings, the first were born in Mexico, another was born in Iraq, and died, and then I was born, and the other four, back again in Mexico,” said Casab, former president of the National Academy of History and Geography.

In Mexico, surnames such as Casab, Manzur, Kuri, Salim, Hakim, Murat, Davish, Odish, Habib, Abud and Hedo, among others, come from those Iraqi Christian migrants, who decided to become Mexicans.

“I carry my boundless admiration for the first Iraqi Chaldean and Assyrian emigrants, who gave us life, homeland and a better future, by blending and integrating fully and deeply into the daily life (of Mexico). This blessed country became our home.

“The other endearing half, equal in everything, lives within us, to forge a group of Mexicans descended from Iraqis, who joined with all the strength of their soul and heart, to the great multiethnic, cultural and religious mosaic that makes up our beloved Mexico,” wrote Ulises Casab in his book.

The Long Road From Iraq To Mexico

According to biblical accounts, and the Semitic and Chaldean tradition, the prophet Abraham originated from Ur, in Chaldea, a region of Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq. The evangelization of this area began in the first century AD.

One of the most important Christian communities, known today as the Chaldean Church, was founded by St. Thomas around the year 90, and later became a religious community, recognized by the Catholic Church today as part of the Churches of the East.

Wars, Muslim fundamentalism and economic crises have led hundreds of thousands of Iraqi Christians to leave their country in the last hundred years, and a group of them, from Telqef and Mosul, chose Mexico to start a new life.

“My father, Tobias Casab, left Telqef shortly after his 12th birthday and a few months, it was 1909 and went first to Mosul, a city with a strong and influential Kurdish population, coexisting with other communities and beliefs.

“From Mosul they went to Baghdad, with other migrants, going in a caravan along the river route and then crossing the great Syrian desert, until they entered the very beautiful and Arabesque Damascus, which is at the crossroads of all the roads in the world,” Ulysses Casab related.

Later, these migrants would arrive in Lebanon to travel by boat to Marseilles, France, and from there again by boat to cross the Strait of Gibraltar, sail across the Atlantic, to finally arrive, some to New York and others to Veracruz.

The writer Ulises Casab, who is 88 years old today, recorded the stories of his father, Tobias, in 1964 with a Japanese Matsuchita Panasonic tape recorder and it was he who gave him the details of his trip to Mexico along with his family.

“Many worked as porters or waiters, to make up the cost of the trip to America or to pay for the disembarkation to land. The maritime stretch to New York was an obligatory passage for almost all the emigrants, because there were no ocean liners that arrived directly to Veracruz”, says Casab, according to his father’s stories.

Juchitán, The Promised Land

In 1932 there were in the district of Juchitán, Oaxaca, about 25 Catholic Chaldean families, most of them originally from Telqef, and another group, of the first ones that arrived from Iraq, had left for Detroit, United States.

Mostly dedicated to commerce, the Iraqi-Mexicans in Ixtepec, in the Juchitán region, not only learned Spanish, but also Zapotec, a language widely used in the region.

“Zaca’ gule ne riniisi sicari, this phrase in Isthmian Zapotec means: thus I was born and thus I have grown up and refers to Ixtepec,” says Ulises Casab, remembering that his father, Tobias, learned from a young age different phrases in the native languages of the region to trade with the locals.

Casab Rueda tells in his book Los Cristianos de Iraq en México, how the integration of the children of Middle Eastern migrants into the local population was taking place, and how the post-revolutionary regime and liberal thinking contributed to this.

“The coexistence in the elementary public schools, whose instructors propagated liberal ideas to the students in order to be able to fend for themselves, enlivened their understanding.

“And that was the most important factor for the children of the Chaldeans and Assyrians to leave the parental blanket, seeking a certain independence,” he related.

“The socio-ethnic integration at school came to fruition when we formed groups of mischief, work, play and study with the natives, and when we grew in size and age, we found ourselves founding modest clubs or pseudo semi-obscure brotherhoods to have a snack, sing and dance,” he pointed out.

Nowadays, the population of Iraqi origin in Mexico has been diluted in the miscegenation that began a hundred years ago, but some of its descendants, like Ulises Casab Rueda, tell the stories that, with pride, make them keep their origin in mind.

“Perhaps there are more than a thousand people with Iraqi blood in Mexico, but these few descendants have tried to contribute in our field to national development. We have participated as what we are: Mexicans in various international forums, representing our country.

“Lately, we have formed a Mexican-Iraqi Cultural Association, with the purpose of preserving the wonderful and beautiful legacy of our Chaldean fathers and, as far as possible, amalgamate it with our rich and beautiful Mexican heritage,” said historian Casab Rueda.

TYT Newsroom