Our Lady of Guadalupe (In Spanish: Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), also known as the “Virgin of Guadalupe,” is a Catholic, Marian apparition and the most venerated image in Mexico. On October 12th, 1895, Pope Leo XIII granted the venerated image a canonical coronation.

The story behind the “Virgen de Guadalupe.”

The Virgin of Guadalupe has been, in addition to religious motivation, a factor of national unity presented by the Catholic Church as the maximum Mexican miracle. However, behind its cult, there is another older one.

The narrative of the “Nican Mopohua,” which means “Here is narrated,” is the oldest manuscript in which the Virgin of Guadalupe’s appearance to the Aztec indigenous Juan Diego is told in the Nahuatl language. There are three versions of the manuscript in the Public Library of New York, but so far is still unknown, which is the original. Researchers of the text conclude that it is written under the style of “auto-sacramental.” A famous liturgical drama of the XVII century, presented religious scenes to evangelize the spectators, in this case, the natives, since they used to transmit their history orally, and a theatrical performance successfully fulfilled the mission of the Franciscan monks.

Tonantzin – The Virgin of Guadalupe

Every December 12th in Mexico, the Virgin of Guadalupe is celebrated, a festivity that, according to the legend, on December 9th, 1531 made an appearance before Juan Diego on Tepeyac’s hill north of Mexico City.

In this meeting, believed by millions of Mexicans, Catholics or not, the Virgin asked Juan Diego to go with Archbishop Fray Juan de Zumarraga of the newly created viceroyalty of New Spain, to build a temple on top of the hill. The friar did not believe in his words and asked for proof. Upon returning to a second divine encounter, the Virgin orders him to take roses on his “tilma” (a type of indigenous clothing garment). When Juan Diego unrolled his “tilma” and let go of the flowers in front of the friar, the miracle happened: The Virgin of Guadalupe miraculously imprinted in the clothes, which has lasted for almost 500 years, currently in the “Basilica of Guadalupe” a story that every Mexican knows since childhood.

Temple to Tonantzin on the hill of Tepeyac

Before the Spanish conquest, there was a temple of adoration to the goddess Tonantzin, which was attended by settlers from all over the Anahuac empire. The federation of tribes was called. Stories collected by the Spanish friars give an account of this: the Mexicas and other Nahua people believed that on the top of the hill of Tepeyac, the mother of the gods appeared:

“The goddess was very venerated by the natives. According to testimonies, she appeared to one of them at a time in the form of a young girl in a white robe and revealed secret things to the person “—Fray Juan de Torquemada in “Monarquía India” – 1615.

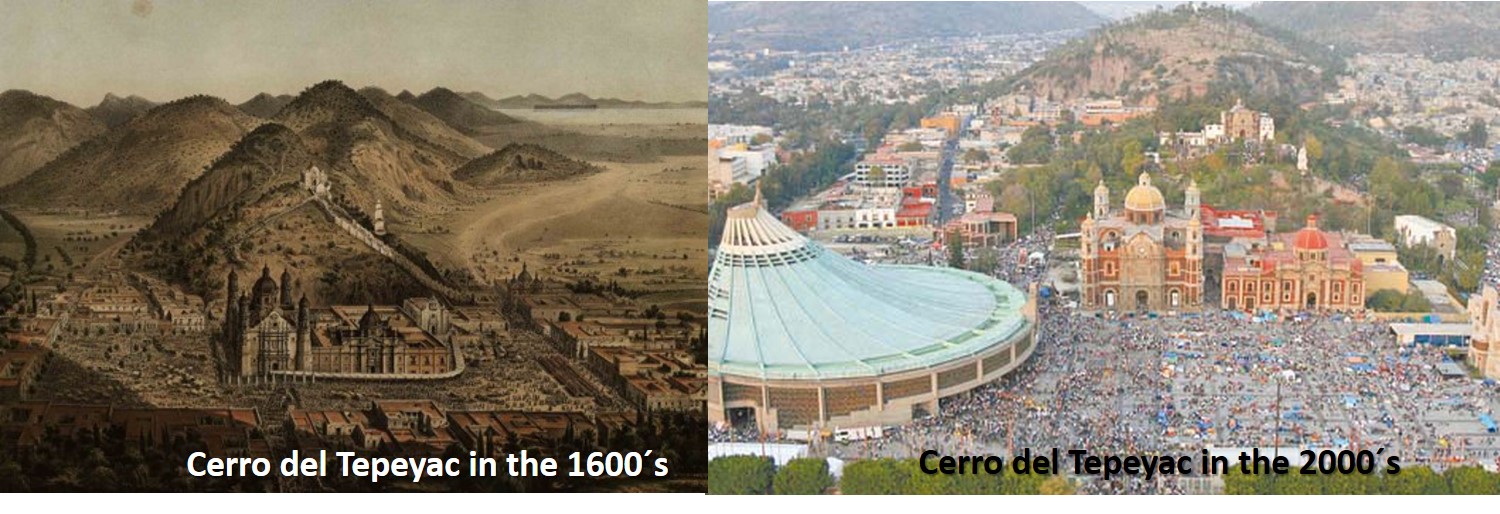

Cerro del Tepeyac

Fray Bernardino de Sahagún said in his texts that in the mountain called Tepeaca or Tepeyac, they had a temple dedicated to all the gods’ mother, they called her Tonantzin, to whom they made many sacrifices. Men and women from all the regions came saying, “Let’s go to Tonantzin’s festivity.”

Tonantzin – The snake woman

The Aztec religion had a mysterious syncretism that researchers have not been able to solve: the mutation of Tonantzin in different names but with the same meaning.

They considered Tonantzin, Coatlicue, Cihuacóatl, or Tetéoinan as “the divine mother”. Some anthropologists believe that under the name of “Cihuacóatl/The Serpent Woman,” this goddess also served as a protector of women.

An ancient Mexican story tells that before the Spaniards’ arrival, a lament of a woman crying was heard in the lake of Texcoco saying: “My children, beloved children of Anahuac, your destruction is next.” The priests thought it was the goddess Cihuacoatl who prophesied the destruction of the Anahuac. Shortly after the Mexica people’s defeat, when the Spanish destroyed the great “Templo Mayor” and Tonantzin’s temple in Mexico City and Tepeyac’s hill, the lament of the goddess was also heard, crying for her dwelling which had been defiled by the invader. This story eventually gave way to the legend of “La Llorona.”

The Spanish Virgin of Guadalupe

In the fourteenth century in the province of Cáceres Spain, on the banks of the “Guadalupe River” -a word of Moor (Arabic) and Latin origin meaning “river of wolves” – Wad-al/river and Lupus/wolves-, a legend was developed which tells that the shepherd Gil Cordero found a brown statuette of the Virgin Mary, who is said to have worked several miracles in that region. Years later, during the conquest of America was designated by Spain’s Catholic Kings as a protector of the Indians of the New World as it was of dark complexion.

Hernán Cortés, the conqueror of Tenochtitlan, carried the standard of the Virgin of Extremadura, of which he was a faithful devotee since he came from the Guadalupan region.

The Mexican historian Edmundo O’Gorman warns in some of his notes that by the year 1530, the Franciscan friars built a hermitage dedicated to the Spanish Virgin, trying to replace a pagan rite with a Catholic one.

The image of the Virgin of Guadalupe

The miraculous legend of the image captured in the tilma of Indigenous Juan Diego takes another more objective vision when the symbols manifested in the image are analyzed since it contained elements of totally pre-Hispanic ideas, represented with Catholic symbols. For example, it includes rhetorics such as “La Flor y el Canto,” one of the philosophies of the Aztec world.

The history of the Guadalupan myth takes on a different force when we remember the cult of Tonantzin, from the perspective with which the beautiful rhetorical resources of Nahuatl poetry are written in the reading of the “Nican-Mopohua.”

Given the above, the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe for most Mexicans, is no longer questionable, much less whether the appearances are real or not. The core of this epic story lies, rather, in that deep religious feeling that has continued for more than 500 years to bring millions of people to the Basilica of Tepeyac to ask favors from the Virgin and her miraculous intervention and help to heal our woes.

The fidelity to the Virgin of Guadalupe cult enriches and provides spiritual elements with a root entirely originated before the conquest – a tradition of faith, ritual, and myth – and the rich Aztec culture.

The Mexicans embrace this syncretism into a melting pot where the old meets the modern world… but still grasp its Guadalupan faith.

TYT Newsroom