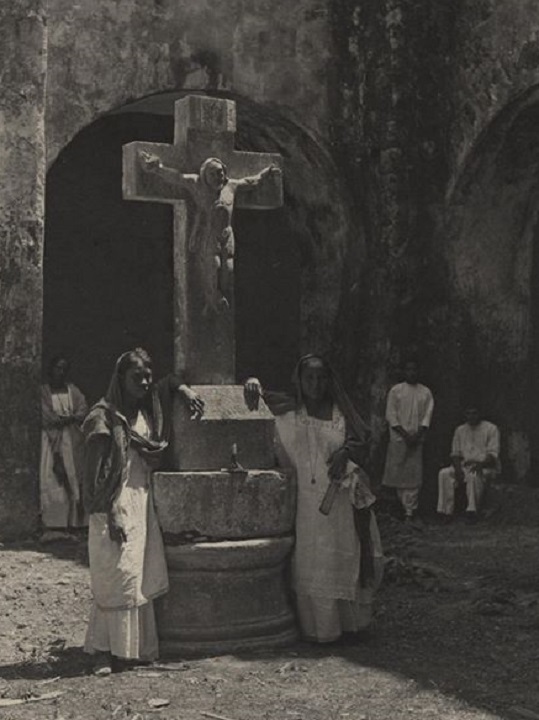

This beautiful stone crucifix, most likely from the 16th century, is an invaluable piece of early colonial art in the Yucatan given its use as an atrial cross, as well as due to the sculptural elements represented on it.

The characteristic of this sculptural piece is that the carved Christ is very reminiscent of the physique of the Mayan man, and at the side, the mooring of the skirt constitutes a bag (sabucan) from which three ears of corn emerge. What better way to enter the Mayan people, dedicated to agriculture par excellence, than to represent a similar farmer Christ in the body and with the cultural (and alimentary) elements of corn?

Its consideration as an atrial cross is not old since it was believed that these didactic resources for evangelization did not exist in Yucatan. The Mani Cross is very different from those in the central part of the “New Spain”, more stylized and featuring the symbols of the “Passion of Christ”, and not a crucifix as is the case with the Mani Cross. However, we have demonstrated its didactic function, similar to the others mentioned.

Its probable origin can be seen as an element used to reinforce the evangelizing campaign after the meeting of the Franciscans in September 1562, in which the religious accepted the failure of the methods employed until then in evangelization. The relationship between the object and the subject, that is, the sculpture and the native, is reflected in the indications of Bishop Francisco Toral, of the same time.

The Franciscan bishop pointed out: “Put crosses at the entrances and exits of the villages and patios and let the Indians understand how they should reverence the crosses, remembering how Christ Our Lord worked in it the mystery of our redemption, and on arriving at the cross they should kneel down and adore Our Lord Jesus Christ alleging the eyes of the soul to the contemplation of this mystery”.

However, if we think that this work was the product of the above-mentioned measures, then why did this type of sculpture did not proliferate in Yucatan? It could be thought that the sculpture of the crucified Indian was a sui generis idea of the site of Mani, the place where the work was conceived to combat idolatry and improve evangelization, using the didactic mechanisms of the atrial crosses in the center of the viceroyalty of New Spain. At that time the village belonged to the Crown since Francisco de Montejo had lost it as an errand for various reasons.

The size of this piece of “sacro-art” 2.40 meters high, with the inscription INRI (Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum) on the top and at a shallow depth. The transversal width is 84 centimeters and its thickness is 15.5 centimeters, both on the side and the front. The immediate base measures 42 cms. high by 52.5 cms. wide, and the lower base is 58 cms. high. The body is symmetrical, except for the hands, feet and head, since it is 79 cms. high and the extension of both arms is the same length.

The symbiosis presented in this work should not have been random and without the approval of the friars, but the religious should have known or been helped by some person(s) to handle the “meanings” implicit in the form and content of this sculpture. The discursive text implicit in the religious work is unparalleled in the region.

Source: J. Victoria Ojeda, 16th Century Sculpture in the Yucatan the case of the Indigenous Christ of Mani, Institute of Culture of Yucatan, 1991.

For The Yucatan Times

Jorge Victoria Ojeda Ph.D

Anthropologist, historian, investigator, author.

With a doctorate in anthropology from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and a Ph.D. in History from Universitat Jaume I, Castellón, in Spain, Jorge Victoria has been the technical subdirector of the General Archive of the State of Yucatan, the head of the Historical Archive of Merida and the director of the Museum of Popular Art of Yucatan. He is currently a professor and works in the Social Sciences Unit of the Regional Research Center of the Autonomous University of Yucatan.

With a doctorate in anthropology from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and a Ph.D. in History from Universitat Jaume I, Castellón, in Spain, Jorge Victoria has been the technical subdirector of the General Archive of the State of Yucatan, the head of the Historical Archive of Merida and the director of the Museum of Popular Art of Yucatan. He is currently a professor and works in the Social Sciences Unit of the Regional Research Center of the Autonomous University of Yucatan.

Dr. Victoria has published fifteen books and numerous articles in Mexico and abroad.

His research on “piracy and pirates in the Yucatan Peninsula” and “Africans and Afro-descendants” has earned him international awards and recognition.